TUSCALOOSA, Ala.—Grant Long never thought he’d be in the audience of a U.S. presidential debate.

But last week, Long, a 19-year-old University of Alabama freshman, took his seat at what was the state’s first-ever debate for the nation’s top office—a GOP primary match-up that did not include the party’s frontrunner—and prepared for the show.

“I was honored to get to be there,” Long said. His role as treasurer of the school’s Republican student group had helped secure his spot in the debate hall audience.

The debate in Alabama hadn’t been a sure thing. For months, Republicans in the deep red state had watched as other, larger cities—from Milwaukee to Miami—secured debate nights. But eventually, the announcement came. The University of Alabama, a college comfortable in the national media spotlight, would host the fourth GOP primary matchup.

But even in a state where Trump beat Biden by 25 points in the 2020 election, Long, like other University of Alabama students Inside Climate News interviewed, wasn’t particularly moved by the night’s sole mention of climate change: businessman Vivek Ramaswamy’s unfounded claim near the debate’s conclusion that “the climate change agenda is a hoax.” There was even mixed reaction in the room, he said.

Alabama students on both sides of the political aisle said that in the reality of today’s world and political environment, one mention of a pressing global issue simply won’t suffice.

“Whether the candidates feel passionately about it or not, this is what the people care about,” Long said. “It doesn’t seem like it’s going away.”

A.J. Bauer, an assistant professor in UA’s Department of Journalism and Creative Media who studies right-wing media and political communication, said the debate demonstrated the distance between Republican Party rhetoric on climate change and public opinion, especially among younger Americans, which has been shaped by the harsh scientific reality of a warming planet.

“Increasingly, public opinion is disconnected from any effect on government,” Bauer said. “What we have is no longer a democracy, and I think that that’s the question that we really need to ask. Why did our democracy go away? Did we ever have one? And can we get one back?”

From the Dairy Farm to the Deep South

Long loves the land. It’s one of the reasons he wanted to come to Alabama for college from his rural hometown in southern Michigan.

Long grew up on his family’s dairy farm. His father had decided to farm, like his father had before him, after teaching elementary school math for a few years. His mother grew up closer to Detroit, an upbringing reflected in her political views, which were much more liberal than those of his father, Long explained.

Politics wasn’t discussed much growing up, Long explained, but he’d always felt that taking care of the environment was an important value.

“As Christians, we had a great appreciation for creation and for God’s provisions for us,” he said. “And so, although we weren’t talking about climate change and carbon emissions, we definitely understood that it’s man’s responsibility to take care of the earth and treat it with respect.”

Long, now a math and economics major, said those values should translate to action, too.

“We should treat the earth sustainably and in a way that leaves it just as good as it should be for the future,” he said.

When the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the globe in 2020, Long was a freshman in high school. He said his family’s experiences during the pandemic shaped their political views in ways no other issue had before.

“COVID rocked my world,” Long said. “I was no longer able to see a lot of my friends. I was a very social person, so that was very impactful to me.”

As the pandemic unfolded, Long said he felt the media was misleading the public.

“In the media, I felt like I had always been lied to,” he said. “I felt like that was kind of an insult to my intelligence.”

Long said his mother, a nurse, felt as though some media portrayals of COVID-19 were alarmist. What she saw on the news, Long’s mother told him, didn’t match what she was seeing in her day-to-day work.

“So there became this weariness among the family members of what else is the media possibly fabricating or painting in a slightly different picture,” he said. “We all became a bit more skeptical.”

These dynamics shifted the Long family to the right politically, a change that would eventually lead Long to his seat in the audience of a national Republican debate.

Debating in Dixie

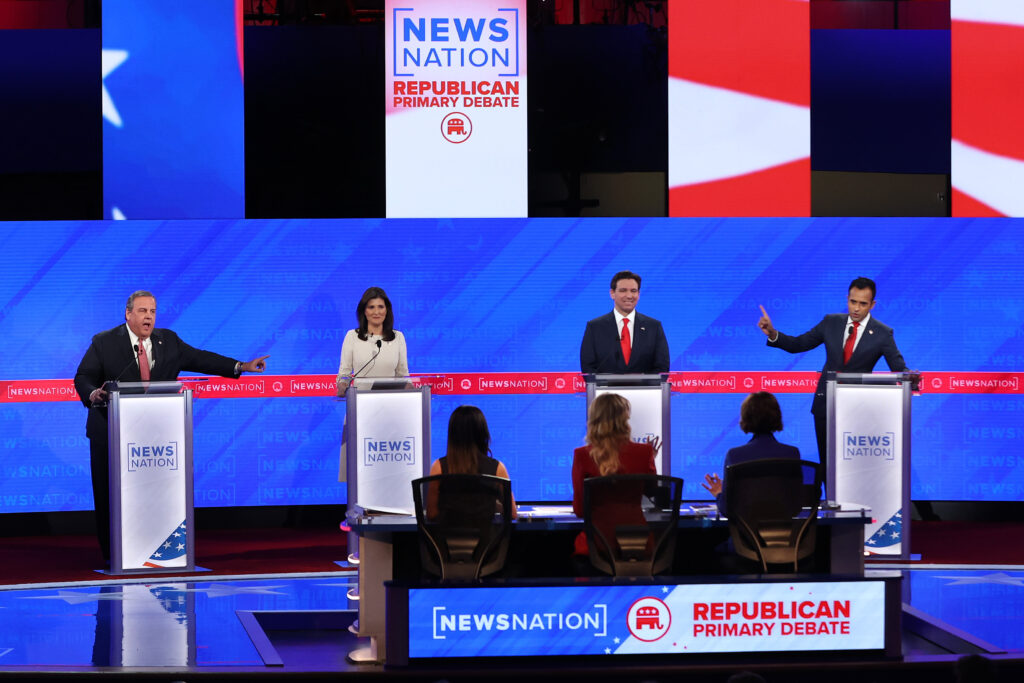

While Wednesday’s debate in Tuscaloosa may have marked the state’s first, Alabama didn’t garner much attention during the debate itself. Sen. Katie Britt, a UA graduate, announced her endorsement of former Pres. Donald J. Trump just before the debate even though the GOP frontrunner chose not to appear in Alabama on Wednesday as his competitors took the stage in UA’s Moody Music Building.

Despite a three-hour debate, climate change did not come up Wednesday night until Ramaswamy, a businessman, raised the topic in closing remarks that spoke to anxieties about government COVID policies like those expressed by Long’s family.

“Just to address a topic we didn’t talk about tonight, but I think is one of the most important topics that needs to be discussed,” he said. “That is this climate change agenda that is shackling this country like a set of handcuffs. I said it at the first debate, and I stand by it. The climate change agenda is a hoax because it has nothing to do with the climate… If you thought COVID was bad, what’s coming with this climate agenda is far worse. We should not be bending the knee to this new religion. That is what it is. It is a substitute for a modern religion. We are flogging ourselves and losing our modern way of life bowing to this new god of climate, and that will end on my watch.”

Long said the reaction to Ramaswamy in the room was mixed, a sentiment he thought was reflective of a divide in the party at large on climate and environmental issues.

“There are people with strong conservative backgrounds that are very much environmentalists and are firm climate change activists,” he said.

Personally, Long said he felt like like he lacked enough knowledge on climate science and environmental policy to have a meaningful opinion on Ramaswamy’s comments.

“I would not be one to come out and say it’s a hoax right now, because I’m not educated enough to take such a concrete stance on it,” Long said. “And as a result of that, I’m also not able to stand here and say he’s entirely wrong. It’s something I do need to look more into.”

From Demagoguery to Useful Discussion

That gap in knowledge—one that could impact national climate policy—is something that has frustrated Benjamin Trost.

Trost, a junior ecology major at the University of Alabama,grew up in Tuscaloosa, the son of two university professors. He remembers talking about climate change during his time in the college town’s public school system.

“The whole class would look at me like ‘What are you talking about?’” Trost said.

Over time, Trost said he’s begun to believe that more innovation in science communication is necessary to effectively inform voters about issues involving climate and the environment.

“I used to ask ‘Why can’t you just look at the science? It’s real,’” he said. “Increasingly, I feel like there’s a science communication issue. There’s some breakdown happening in the communication between the scientists and people who are rejecting that information.”

Much of that breakdown, Trost said, is caused by politics. For him, that realization has stoked an interest in understanding the best ways to move public opinion forward on environmental issues. Trost said he’s likely to vote for Biden in the 2024 presidential election but that everyone—Republican and Democrat–-should aim to have more nuanced discussions about our changing climate.

“How do we have more useful conversations about climate change that aren’t going to be politically divisive but can instead convince more people?” Trost asked.

Compassion, Trost said, can go a long way.

“There are ways to communicate the science that don’t give people the same hair-trigger political reaction,” he said. “I would love to see those conversations happening, to be involved in them happening.”

Ramaswamy’s framing of climate change and climate policy as a “hoax,” then, is a step in the wrong direction, Trost said.

“If people aren’t willing to even have a discussion that’s a real discussion—that isn’t performative, that’s not like a circus—then you’re never going to get past it as a politically divisive issue that does nothing but split voters,” he said. “And that’s frustrating.”

Like Long, Trost grew up loving the land. And it’s that love, he said, that’s motivated him to pay attention to environmental issues—not just at a global level, but right here in Tuscaloosa, too.

“I love going to Hurricane Creek,” Trost said. “It’s probably my favorite place to go. But there’s a chronic issue the city has with sewage spills in the area.”

Those types of issues—places where environmental science should spur public policy—are areas where Trost hopes science communicators and the media can do a better job connecting the dots for those without the time or energy to do their own research.

“I’ve also come to realize that addressing environmental concerns without having some kind of political basis can only get you so far,” he said. “It won’t get you the kind of coalitional support you need for real environmental reform.”

For Long, while climate change and environmental issues aren’t at the top of his mind as primary season rolls around, he recognizes that public pressure for policy change won’t simply go away if politicians ignore it.

“To have no stance at all would be to shoot a candidate in the foot,” Long said. “It’s a global issue.”

Bauer said that Long and Trost’s views on Wednesday’s debate reflect the reality that when it comes to climate change and environmental issues, most Americans’ views fall far to the left of GOP politicians’.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now“One of the problems I’m seeing in this broader debate is that it’s been framed as though it’s a public opinion problem: that there’s a disagreement among the public that climate change exists and something should be done about it,” Bauer said. “The polls suggest otherwise. The public believes that climate change exists. They believe that something should be done about it. What remains, then, is not a public relations problem, but a political problem.”

Conservative voters may sometimes find themselves dealing with cognitive dissonance because of how climate and environmental policy have been weaponized by politicians on the right in ways that may not match voters’ fundamental beliefs, Bauer said.

“On the one hand, they have this kind of clear ideological vision that believes in Christian stewardship of the land,” Bauer said. “But at the same time, they’ve got a lot of headwinds of Republican politicians that they trust on issues more broadly saying, well, these people are evil and are actually doing the bidding of Satan.”

In the end, Bauer said the climate change rhetoric on the right isn’t about ideology.

“It’s about scaring people from using government resources to mitigate climate change in ways that might be bad for business fossil fuel companies,” Bauer said.

What’s left, then, is a governance problem, Bauer explained.

“To what extent are public officials willing to disrupt the ongoing cycle of global capitalism to keep us all alive?” He asked. “Thus far, there has been relatively little willingness of governmental agencies, of people who work for the government to actually engage in meaningful mitigation efforts. That’s the real problem.”

He said while there’s been some media attention around the GOP holding the debate on a college campus as a means of courting or even touting support among young voters, the limited number of general student tickets to the event speaks for itself.

“It suggests that they’re not really that interested in what students think, beyond giving conservative students an opportunity to rub elbows with the kind of party elite,” Bauer said.

Bauer said there’s been no real effort on the part of GOP candidates to meet young voters where they’re at on climate and environmental issues. Meaningful youth outreach, he said, means more than just showing up on campus for a one-time, ticketed event.

“And frankly, there’s just not much evidence of more than that,” he said.